A Word: War

by Kateryna Iakovlenko

There is no place for poetry in war, yet the war has given rise to new forms of poetry. Ruined and abandoned houses, gutted forests, shelled land, and roads scarred by tank tracks began to resemble letters and unwritten sentences. Will someone add to them, cross them out, rewrite them, or throw them away like a crumpled piece of paper?

Us - You - Them

by Haska Shyyan

Translated from the Ukrainian by Kate Tsurkan and Yulia Lyubka

I'm not one to get nostalgic often, so it came as a surprise to me when I was overtaken by an intense and illogical longing to be in Ukraine during those early days of the full-scale invasion; the direness of the situation would likely have resulted in my fleeing to where I already am. I think this desire stemmed from my need to verify the truth of what was happening on my phone screen, which I carefully concealed from my child, pretending to be idly watching something while at work.

The Roots of War

by Yuliya Iliukha

Translated from the Ukrainian by Kate Tsurkan and Yulia Lyubka

As we drove the familiar route that I had traveled for years, I could list all the villages that dotted both sides of the Kyiv highway from memory. I didn't even need to look at the signs. They had been taken down during the first week of the invasion. As we passed Pisochyn, I was ready to start crying. Kharkiv was just a short distance away, and the images and footage I had been scrolling through on Telegram channels day and night left no doubt that my eyes would well up with tears before reaching Kholodna Hora.

My Skin Drifts Away

By Merey Kossyn

Translated from the Kazakh by Mirgul Kali

She began to molt. The particles of skin separated from the naked body on the prayer mat, floated upward, and scattered in the air. A moment later, in perfect unity, they converged again to form a human body, the body of a girl. Reluctant to leave behind its owner, this skin, this ethereal shell of a body, kept circling the praying girl.

My First Bomb Shelter

by Ihor Pomerantsev

Translated from the Ukrainian by Yulia Lyubka and Kate Tsurkan

The train from Lviv to Kyiv arrived at six in the morning. As I stepped off the train, I was greeted by the song “Chestnuts are blooming again.” Soldiers on crutches stood on the platform. Thirty minutes later, I arrived at the hotel in Podil. At seven o’clock the air-raid siren went off. I headed down to the bomb shelter. My American colleagues were already there, so I attempted to translate a poem by the Kyiv poet Semen Hudzenko for them

Explaining Reality

by Grigory Semenchuk

Translated from the Ukrainian by Yulia Lyubka and Kate Tsurkan

“Where are you from?” asks a group of men in expensive suits in the lobby bar of a small British town hotel. “From Ukraine,” I reply. “Wow, Ukraine! Are you here for the literary festival? How do you like it here?” they ask with genuine enthusiasm. “I like it, but I want to go home. I'm worried about my wife, parents, and friends. Yesterday our cities were bombed again all morning,” I explain. “Why do you want to go back? Bring your families here,” they suggest.

The Story of My Light

by Miklós Vámos

Translated from the Hungarian by Ági Bori

I am Hungarian, but that doesn’t mean that I am crying over Trianon or wearing old-fashioned folk costumes. It does mean I am a great admirer of the Hungarian language and, throughout my career, I have used it and its malleability to create my distinctive, multidimensional style. I truly enjoy the elasticity of the language. The Hungarian government? Not so much.

A Matter of the Heart

by Pavlo Matyusha

Making the right choice for your health during times of war is no simple task. It’s an unexpected challenge, much like the sudden sound of shelling. It can force you to reconsider your previous decision to fight for your country, and it’s often accompanied by fear. It’s the fear of what’s yet to come coupled with the longing to take a step back and ponder your life choices.

The War for Decolonization

by Taras Lyuty

Translated from the Ukrainian by Yulia Lyubka and Kate Tsurkan

Russia’s war against Ukraine is also taking place at the cultural level. For years, the Russian empire appropriated the achievements of Ukrainian artists and thinkers. The Ukrainian philosopher Hryhoriy Skovoroda is one such example. In 1912, the Russian philosopher Vladimir Ern wrote a book about him. He called Skovoroda a Russian philosopher, explaining that Ukraine was an uncivilized country, and Russia endowed Skovoroda with the opportunity to develop his talent.

Evil Must Have a Name

by Stanislav Aseyev

Translated from the Ukrainian by Kate Tsurkan and Yulia Lyubka

I’m only 33 years old. In my lifetime I already endured electric-shock torture for 2.5 years in the notorious Russian concentration camp known as Izolyatsia, was released from there on a prisoner exchange, found the concentration camp's commandant right in the center of the Ukrainian capital and had the special services arrest him.

Keto and Kenosis

by Max Lawton

The dead of night and flames on either side made it completely impossible to make out anything but fire as such. That and the question of whether there were even that many trees around Santa Barbara to be set alight; I remembered it more as a sort of desert oasis nestled among low hillocks.

The Enemy

by Roman Malynovsky

Translated from the Ukrainian by Kate Tsurkan and Yulia Lyubka

Going out into the dark forest, there, in the darkness, in the winter silence, is the most terrifying thing. But I nod at this proposal, and so does Marta, followed by Ilya and the rest. We will go there and do what we fear the most because this is such a moment, and each of us feels it the same way: we are strong and confident we will succeed.

Music for a Soldier

by Artem Chekh

Translated from the Ukrainian by Yulia Lyubka and Kate Tsurkan

Music became my main companion in those forests, a mandatory addition to a soldier’s arsenal, just like a personal weapon or a tourniquet. Female singers became the soundtrack of my depression, the hellish nimbus of an eternal struggle between good and evil, the deafening sound of my loneliness, and the shadow of a soldier’s frustration.

Relieving the Terrible Knots of History: An Interview with Alex Averbuch

Interviewed by Sandra Joy Russell

“I have a quite banal belief that poetry is born out of something traumatic, something violent that you have to say in a broken language, to mock this violence, to imitate, to make it approachable, to adjust the words to what you’ve gone through. I don’t think poetry is beautiful; not sure what ‘beauty’ is.”

This war is forever–you hear, Sofi?

by Khrystia Vengryniuk

Translated from the Ukrainian by Yulia Lyubka and Kate Tsurkan

If we forgive, forget, and swallow it down again, as in 2014, our children will have to live through the same things we are going through now; only they will play the leading roles. This evil never sleeps, so our descendants must be constantly ready for everything. Unlike us, who neglected the words of Taras Shevchenko, Mykola Khvylovy, and Vasyl Stus and missed, overlooked, and underestimated them.

Disparate and Distressed Dames: A Review of Ivana Dobrakovová’s Mothers and Truckers (2022, Jantar Publishing)

Reviewed by Anna West

It is the essence of a wandering mind that Dobrakovová captures so aptly. The stories read like confessionals and are told in long train-of-thought clauses separated by commas, with some sentences taking up half the page or more. The stylistic choice helps to pull the reader into the obsessive thoughts of our narrators.

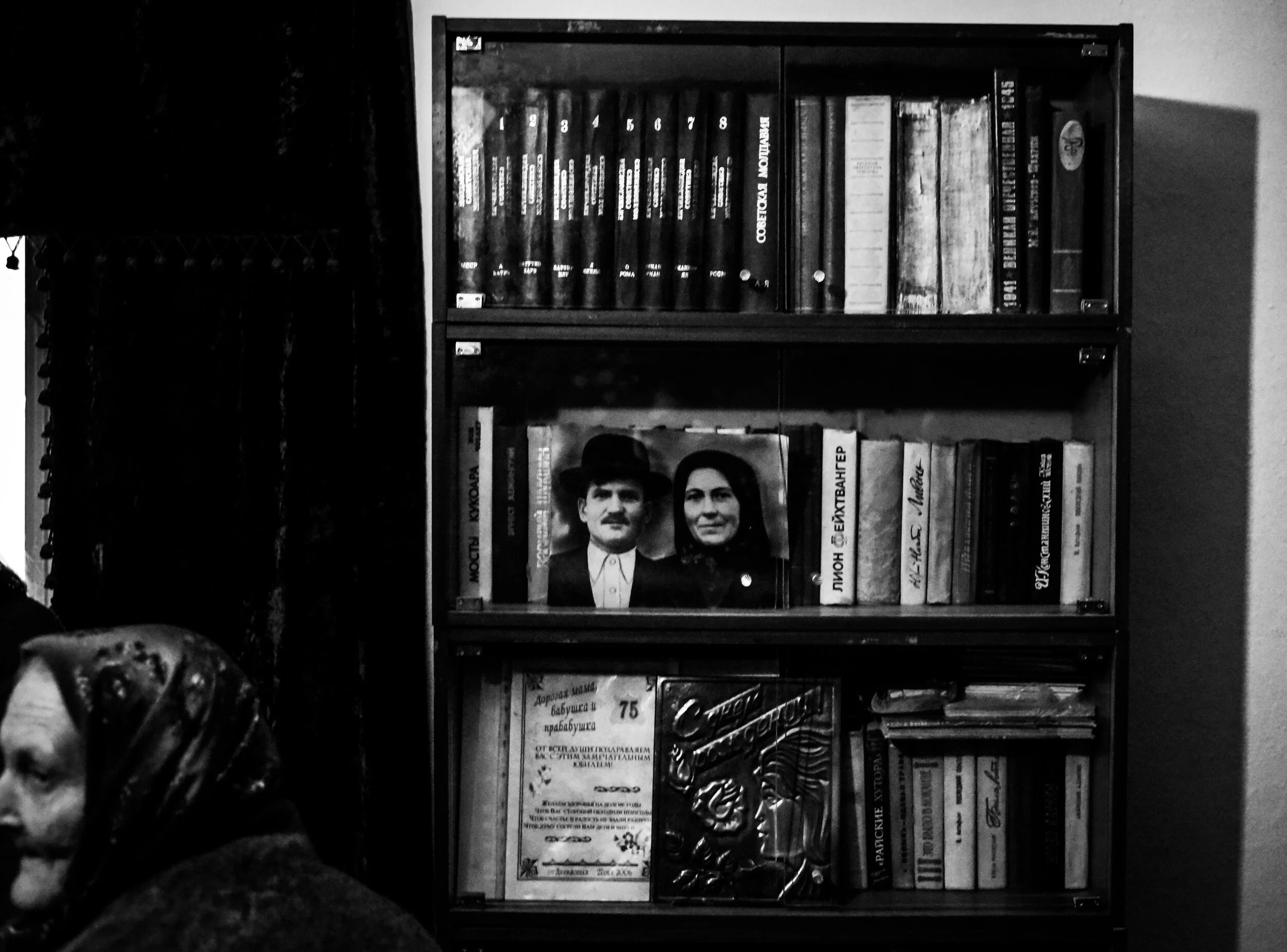

How Russia’s war in Ukraine has changed photography

by Kateryna Sergatskova

Open the online galleries of international agencies like Getty Images or Associated Press, and you'll see that most photographers in Ukraine capture the remnants of missiles, destruction, corpses, and funerals. War forced wedding photographers to capture funeral processions and fashion photographers to take photos of soldiers in the trenches.

Archives, decolonization, and the Ukrainian East: An Interview with Lyuba Yakimchuk

Interviewed by Kate Tsurkan

“I used to find working in the archives uninteresting until I started digging deeper into Mykhaylo Semenko’s life story. You probably know he was a leading figure of Ukrainian Futurist poetry who was shot dead in Kyiv in 1937. The search for documents relating to his life sometimes resembles an investigation.”

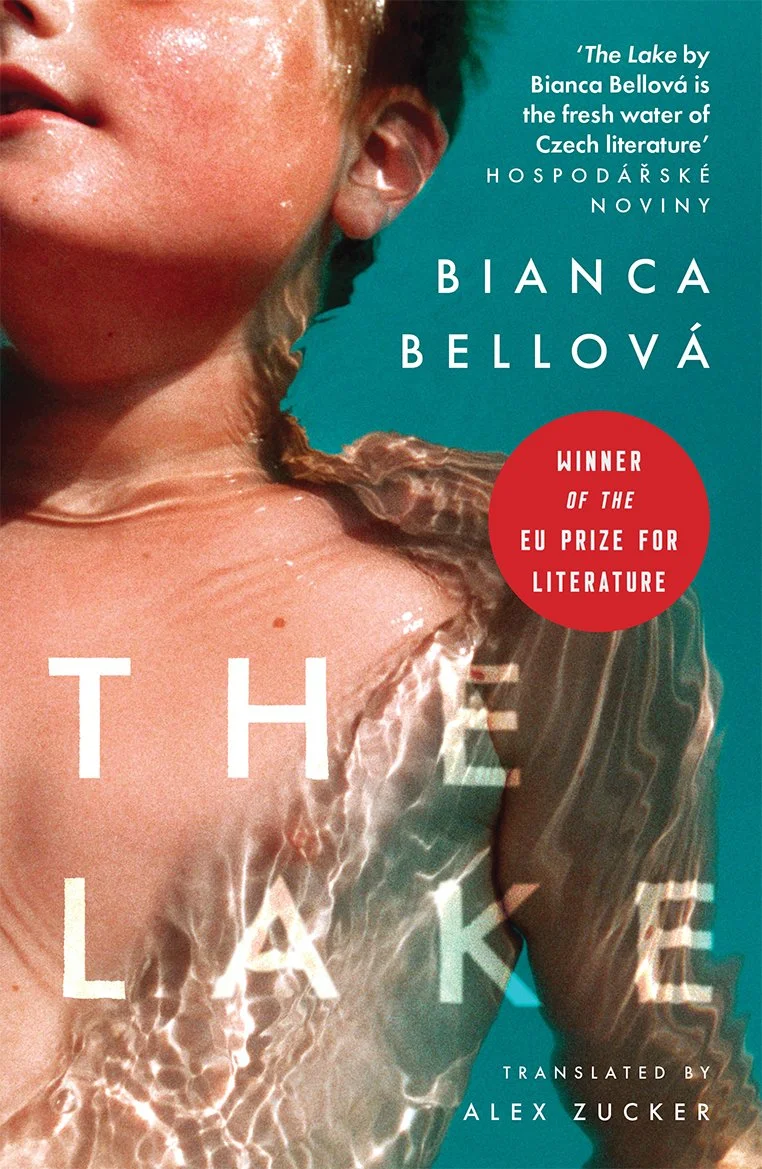

A Review of Bianca Bellová’s The Lake (2022, Parthian Books)

Reviewed by Anna West

Bianca Bellová’s The Lake, translated into English by Alex Zucker, follows Nami as he navigates childhood and young adulthood in a fictitious land made brutal by environmental degradation and Russian occupiers. The Czech author, who grew up in communist Czechoslovakia during the so-called period of normalization in the 1970s, is known for her works that explore themes relating to the communist era.

Life in Switzerland, literary scandals, and helping Ukrainian refugees: An Interview with Oles Ilchenko

Interviewed by Olena Lysenko

“Europeans have already forgotten the reality of war and are very afraid of any form of violence, so they always try to come to an agreement. But it is impossible to peacefully come to an agreement with a nation like Russia. This situation has impacted everyone to a certain extent, and it is no longer possible to say that nothing is happening.”