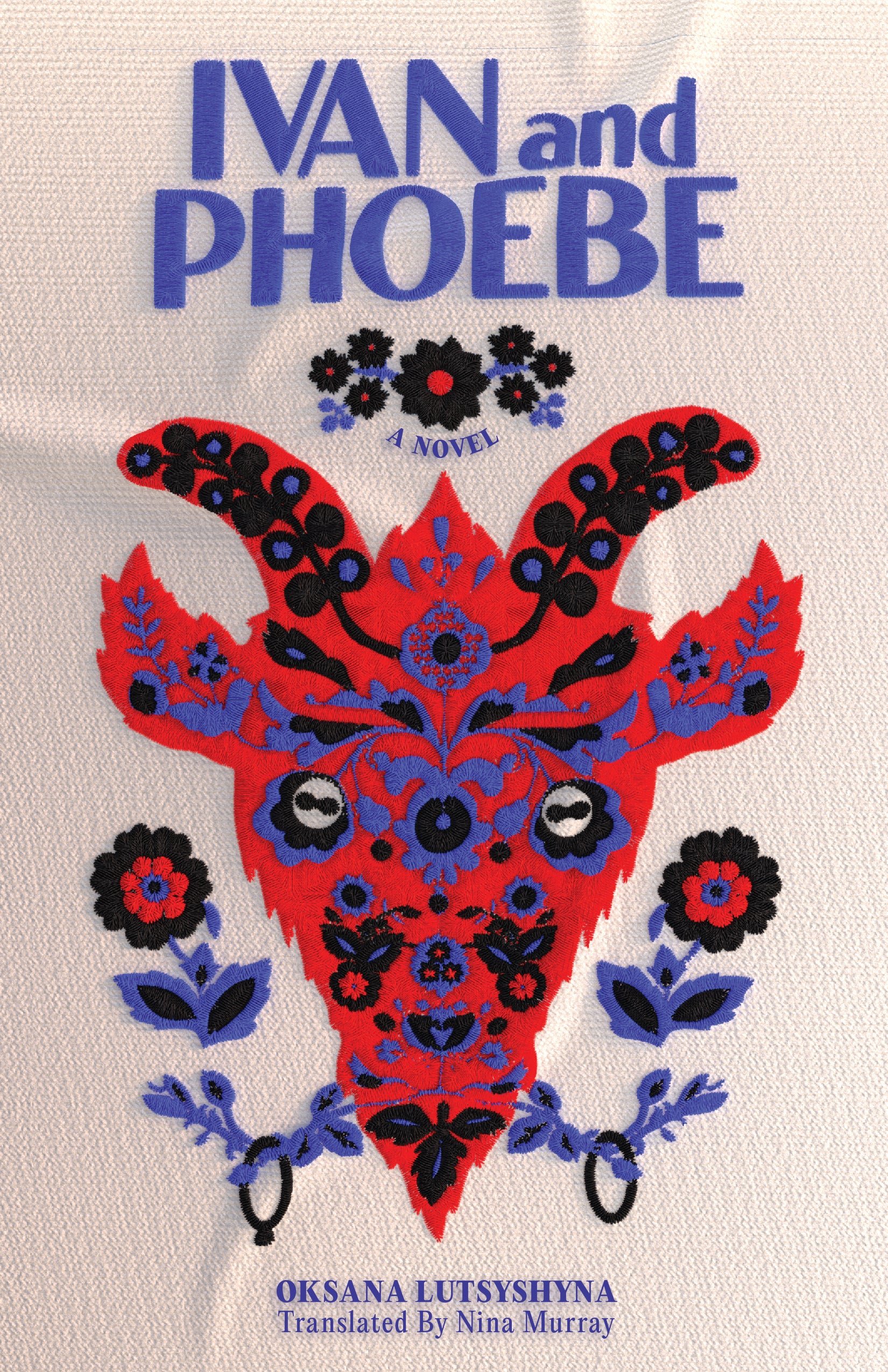

When the Revolution’s Over: A Review of Ivan and Phoebe (2023, Deep Vellum)

by Elsa Court

As Ivan develops into a state of numbness, Lutsyshyna shows what can happen to the heroes of a revolution when the revolution itself is declared over. He reminisces about his past and experiences no hope for the future, only nostalgia. He becomes emotional at remembering his childhood friends, some of whom have left Uzhhorod and another of whom has died of alcoholism.

Unlocking Ukraine: Embroidered QR Codes as Cultural Keys

by Alexandra Keeler

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Kyiv-born master embroiderer Tetiana Protcheva turned her talents toward guerrilla art activism. Blending ancient Ukrainian folk art with cutting-edge technology, Protcheva creates embroidered QR codes loaded with digital resources detailing Ukrainian culture. “My mission is to go around the world and show people Ukraine through embroidery,” she says.

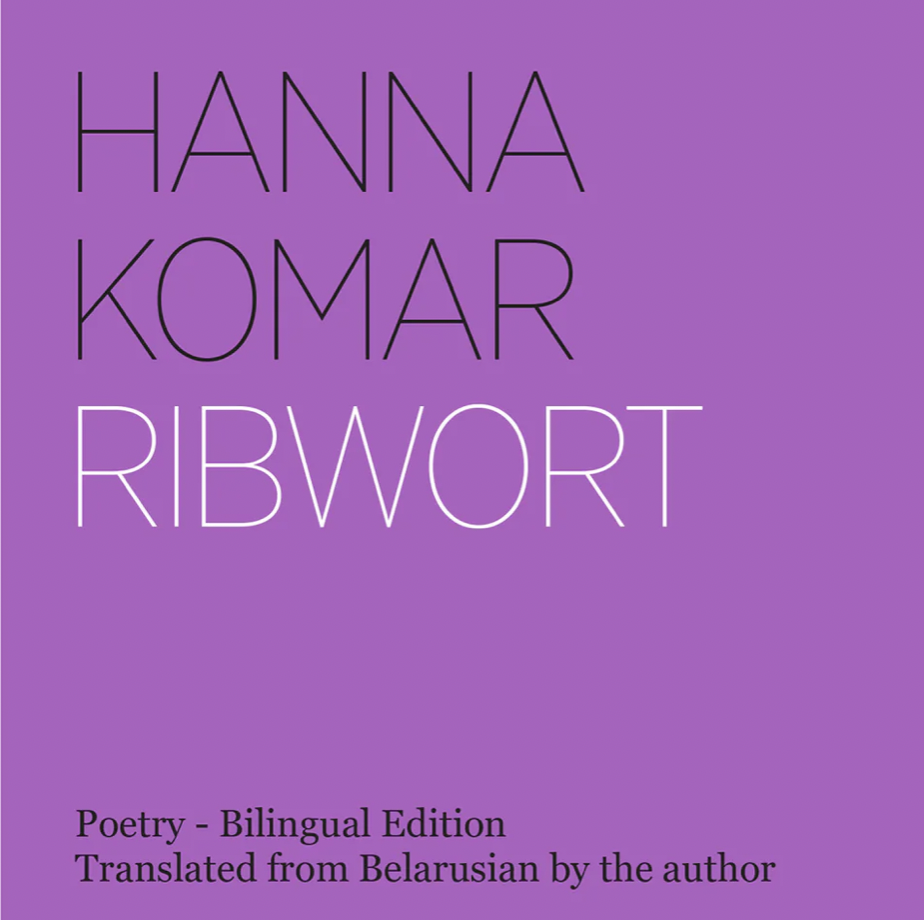

Courage and tenderness: A review of Ribwort by Hanna Komar (2023, 3TimesRebel Press)

Reviewed by John Farndon

The opening words of Hanna Komar’s poetry collection, “wrap around me like ribwort,” grab the reader with courage and tenderness, grief and love, and never let go. Ribwort, a plant revered in Belarus for its potent healing properties in herbal medicine, is a compelling metaphor for the nature of these poems. While rooted in raw honesty and precision, these verses don't shy away from revealing the wounds plaguing the poet and her nation.

Glimpsing the impossible: An Interview with Olesya Khromeychuk

Interviewed by Sonya Bilocerkowycz

“(Ukrainian solidarity) is something that I think people outside of Ukraine struggle to grasp: Why is a Crimean Tatar fighting for Donbas? How is it that a Russophone Ukrainian would rather die fighting than find her- or himself in Russian occupation? Our strength is in unity and it’s this unity against imperial oppression that we’ve been cultivating for generations.”

Beyond Švejk: Jaroslav Hašek’s serious comedic tales

by Anthony Hennen

Jaroslav Hašek’s enduring success as a writer, thanks to his novel The Good Soldier Švejk, left him in an unwarranted one-hit wonder conundrum. A raucous satire about a soldier strongarmed into the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I, the book has been translated into dozens of languages. It remains in the zeitgeist of European literature.

My world stands on pillars

by Kateryna Iakovlenko

Translated from the Ukrainian by Kate Tsurkan

He's nearly thirty, tall, dark-haired, and always smiling. His name is Bohdan, and he was born into a priest's family. He's an artist working with contemporary art, and just a few months ago, you could see his work at the Hanenki Museum, which is located in the former mansion of a sugar beet magnate and collector in the very center of Kyiv. In the military, he goes by the call sign Pillar.

Convoluted Truths about Persistent Evils: A Review of Ján Johanides’s But Crime Does Punish (2022, Karolinum Press)

by Katarina Gephardt

Writing in the 1990s, when many intellectuals were hopeful about the future and ready to leave the past behind, Johanides stressed the continuity between the past and the present, underscoring the continuity of historical evils. However, aspects of the colonel’s and even Ostarok’s characters reflect the writer’s existential hope that individual human choices can alter the course of history.

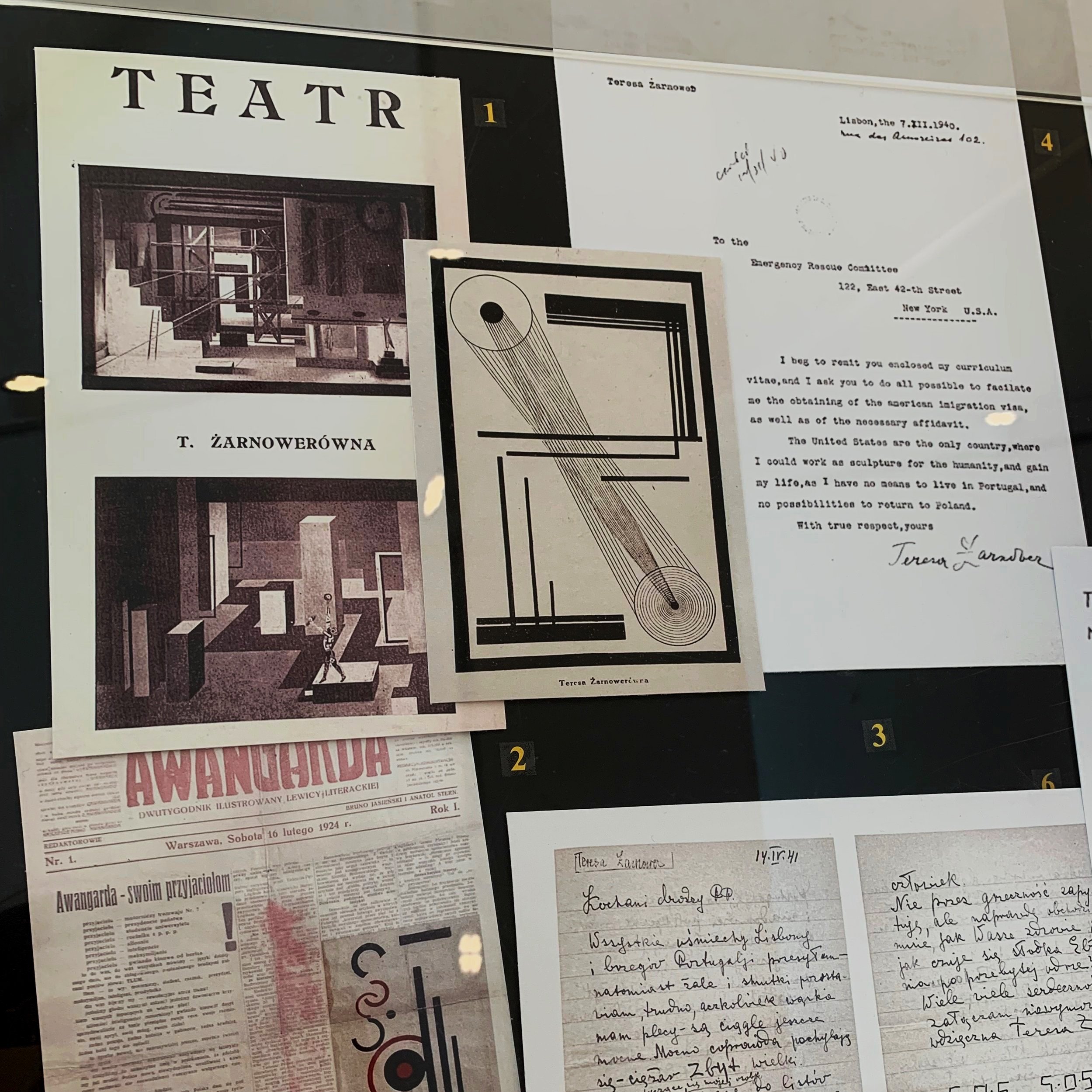

“I Saw the Other Side of the Sun with You”: Female Surrealists from Eastern Europe

by Juliette Bretan

There was something about placing these artworks together in Cromwell Place – one of those ubiquitous wedding-cake-style townhouses of high Kensington, all whitewashed walls, floor-to-ceiling windows, and clean spotlighting – that made this exhibition, somehow, even stranger; as if each artwork fractures something of reality, or allows a glimpse into another form of it.

Emerging from the Space of Noise: An Interview with Iryna Shuvalova

Interviewed by Anna Gruver

“As a poet, death interests me as intensely and deeply as any other life experience I encounter. In that sense, there are no taboos for me: what can be touched upon and what cannot, what I write about and what I don't.”

A centuries-long tradition, a symbol of defiance

by Sofika Zielyk

In a few days, I will go to the cemetery with a basket of Ukrainian Easter eggs. In my culture, it is a tradition to place these eggs, called pysanky, and Easter bread on the graves of departed loved ones so that we can symbolically partake in the Easter feast together. This year, however, will be a little different.

Ukrainian traditions, decolonization, and reporting from Bakhmut: An Interview with Myroslav Laiuk

Interviewed by Olena Lysenko

“In Bakhmut, people have grown accustomed to sleeping in houses with broken windows, simply covering themselves with a few blankets. These are the harsh realities that currently have no solution. The unfortunate truth of our current reality is that people can become accustomed to living in a war zone.”

High Tea at the Kapurs'

by Karuna Ezara Parikh

She tells me and my college friend from London

– Diana, ‘like the princess!’ Aunty says –

that ‘nowadays it’s only for marriage,

like we are Khatri, we want Karan also to marry Khatri.’

Diana asks why, as I dip Pure Magic in chai,

but Karan comes in, bringing with him hot-hot air,

‘Bhenchod’ he says, and tells us how the ‘bloody driver’ has been unfair.

Caste and Language: An Interview with Karuna Ezara Parikh

Interviewed by Iryna Verano

“It took me a long time to question my own caste identity. Sometimes consciousness works that way too. An ultra-liberal approach argues that we fail to see caste because we oppose it. But that, too, is problematic, and over the years, I have learned to see it, accept it, feel the embarrassment of it, and then work from that place of recognition, which I find healthier than the previous approach, which was uninformed.”

Diary of Silence

by Victoria Amelina

Translated from the Ukrainian by Yulia Lyubka and Kate Tsurkan

Since the start of the war, I have developed a cough – it chokes me as soon as I try to say something long and meaningful. Some say it's psychosomatic, while others say it’s because I sleep on the floor. Refugees sleep on the beds and sofas in my Lviv apartment (they say it's better to call them “new neighbors”, and that it's also better to keep quiet about the fact that they are refugees or IDPs).

Philsophies

by S.T. Bryant

Othello teaches, contra Descartes, that we are perpetually,

to our precarious doom, unaware of that deepest in our hearts.

We are planetary, too planetary, orbital, to be so singular.

Always susceptible to annihilative ruminations, motives.

Our happiest times, our Monism, prey us to destruction.

Further From Peace, Closer to Victory

by Iya Kiva

Translated from the Ukrainian by Yulia Lyubka and Kate Tsurkan

Time has never felt as heavy as it does now. It's like carrying a gravestone on your shoulders, bending your spine and distorting every step, an unshakeable weight that cannot be thrown off, like those with back problems cannot find comfort, trapped in the torture chamber of their own bodies.

A Word: War

by Kateryna Iakovlenko

There is no place for poetry in war, yet the war has given rise to new forms of poetry. Ruined and abandoned houses, gutted forests, shelled land, and roads scarred by tank tracks began to resemble letters and unwritten sentences. Will someone add to them, cross them out, rewrite them, or throw them away like a crumpled piece of paper?

Us - You - Them

by Haska Shyyan

Translated from the Ukrainian by Kate Tsurkan and Yulia Lyubka

I'm not one to get nostalgic often, so it came as a surprise to me when I was overtaken by an intense and illogical longing to be in Ukraine during those early days of the full-scale invasion; the direness of the situation would likely have resulted in my fleeing to where I already am. I think this desire stemmed from my need to verify the truth of what was happening on my phone screen, which I carefully concealed from my child, pretending to be idly watching something while at work.

The Roots of War

by Yuliya Iliukha

Translated from the Ukrainian by Kate Tsurkan and Yulia Lyubka

As we drove the familiar route that I had traveled for years, I could list all the villages that dotted both sides of the Kyiv highway from memory. I didn't even need to look at the signs. They had been taken down during the first week of the invasion. As we passed Pisochyn, I was ready to start crying. Kharkiv was just a short distance away, and the images and footage I had been scrolling through on Telegram channels day and night left no doubt that my eyes would well up with tears before reaching Kholodna Hora.