Language, war, and cruelty — an interview with Romanian Moldovan novelist Tatiana Țîbuleac

A former journalist reporting on social issues, the European Literature Prize winning Tatiana Țîbuleac is one of the most read and beloved Romanian language authors thanks to her two poetic, entrancing novels, The Summer When Mother Had Green Eyes (2016) and The Glass Garden (2018). The books have been translated in 15 languages, with great success in the Hispanic world, where The Summer When Mother Had Green Eyes has had its 11th edition printed. Born and raised in Chișinău, in Soviet Moldova, in 1978, Țîbuleac now lives in France with her family. Below, Paula Erizanu and the author discussed womanhood, generational change, Soviet-era Russification, the war in Ukraine and the ensuing refugee crisis. Further down, you can also read an extract from Țîbuleac's novel, The Glass Garden.

Dear Tatiana, your novel The Glass Garden engages with the Soviet occupation of Moldova through the story of a Romanian-speaking girl, abandoned by her parents and adopted by a Russian-speaking woman. You mentioned in an interview that this book helped you come to terms with the past. Has the war in Ukraine changed your perspective and relationship to the book?

I wrote this book almost 30 years after the collapse of the USSR, after 10 years of emigration and after giving birth to two children in a foreign country. Maybe at first glance all these things have nothing in common, but they do. It was important for me to look at the balance sheet of my identity, to see how much of my own past and my family's past should be passed on to my children and in what form. My mother was born in the Siberian Gulag, where my grandparents were deported as "enemies of the people." My father lived his whole life with the hope that Moldova would be reunited with Romania and that it would escape Russian influence forever. The war in Ukraine was his biggest fear, he always said that this will happen in Moldova, that Russia will never give up the idea of reviving the Soviet empire. He was right; maybe it's better that he died before he saw all this. There is a lot of hatred and bitterness gathered in our family towards Russia, and I, born in the USSR and partly raised in a Russified neighbourhood and environment in Chișinău, was always the weak link. It was hard for me to hate a language in which I read stories, made friends and fell in love for the first time. In the years when Romanian literature was almost completely absent at school, Russian was also the language that opened a window to universal literature, to films, theater, and, as strange as it may sound, to the West. We know the price for this "opening": we paid it.

Before writing The Glass Garden I spoke to many people of my generation, mostly migrants, who felt as I did, in that it was vital to separate a language from a political regime. Are you asking me what has changed now? In a way, I should be able to say nothing — I still believe that a language is a communication rather than a political tool — but that would be wrong, because in fact everything has changed. I'm afraid that the discussions about Russia and the "Slavic soul" is just beginning, and that it's a debate that will last for decades, and not just in our part of the world. The truth is that no one can force you to relate to a language in a certain way, no sanction, no court can convince you to love or hate a language. If this does not happen by itself, if you yourself do not feel strange reading or speaking Russian, while in Ukraine Russia is killing people, including in the name of this language, then you have one less problem. Personally, I can only say one thing — I am closer to those who grew up with Russian, but who are now moving away from it, as a sign of human and ideological protest, than I am to those who claim that Russian never mattered to them.

On the absence of Romanian language books — when they were students in the 80s, my parents, like many in their generation, went to Odesa or Chernivtsi for Romanian books because they were not to be found in Moldova. What was your case, did you have access to them?

I grew up with the belief that danger comes from books. It was a strange feeling, even exciting, and I often wonder whether that wasn't part of the charm books bore for me — to be afraid of something that attracted me the most. I had school books and books that I only read at home. At home we kept Romanian books, like all the families of intellectuals did. We hid them under the sofas; we had a false wall in the bathroom, but we took most of them to my grandmother in the countryside. Grandma kept them in the drawing room (called casa mare, translated literally as big house even if usually it was just a room), hidden in the chest, behind headscarves and holiday clothes. She didn't really like this job. For her, casa mare was holy, and those books there, with their long life, were in themselves a sin. My father taught me to read the Latin script before the Cyrillic alphabet. But I wasn't allowed to talk about it at school. But we, the children who read books in Romanian, knew each other. Even if we were not friends, we had a feeling of solidarity with each other.

The woman adopting Lastocika in your novel is a glass picker. While supporting and raising the child, she also sometimes treats her with cruelty and even exploits her — although it's hard to talk about exploitation in the case of poor parents who also put their children to work, in order to survive (I'm thinking, for example, of my great-grandmother, who didn't go to school after fourth grade because her parents needed her to look after the animals; she resented them all her life; at the same time, without her help, her family may not have managed to get by).

I'm glad we can discuss about a concrete person — here, a great-grandmother! — especially since such women of sacrifice existed in almost all Eastern European families. Girls from poor or large families were the first to give up their education – either for economic reasons, or because of the prejudice that a girl is better off having children, not a diploma. Some were sacrificed twice — once when they did not go to school, the second time when they were forced to marry young or for money. This was the case of my grandmother; if we're still talking about grandparents, bless them! Returning to the period described in the book, the problem of studies was no longer an issue then, as secondary education became compulsory in the Soviet Union for all children.

When I wrote The Glass Garden I juggled several important themes for me — identity, generational trauma, bilingualism — important then, but especially now. I never thought that some secondary descriptions, as they seemed at the time, would arouse separate controversies. This happened especially with the translation of the book into other languages. In France I was asked most often about child labour and domestic violence, in Germany about institutional abuse. In the Scandinavian countries we had some extremely interesting discussions on women's mental health and their obligation, sometimes forced by society, to take almost all care of children. It is obvious that in Eastern European countries the readers were more interested in the collective ability to overcome trauma, but at the same time also in the lack of a culture of collective guilt for any kind of atrocities committed in the past. I was once again convinced that a book is read differently in different cultures.

Unfortunately, we can't just talk about many of these things in the past. In Moldova, thousands of children continue to be beaten for educational purposes by their parents or caregivers; in orphanages, which unfortunately still exist, which is a shame in itself, children are sexually abused; girls and women are abused and raped, and society holds them at least partly to blame for it. As you can see, this cruelty in my books, often invoked by critics, is not exactly invented.

My generation grew up with more obligations than rights. Children knew from an early age that they had to take responsibility in the family. Parents were absent almost all of the time, being at work. Older kids raised the younger ones. Children cooked their own meals, went to and from school alone, parents rarely participated in homework or other activities. Children were there a lot more independent than today's generations, but with freedom came responsibility. In the villages, the situation was even more complex. In addition to looking after the young, children also took care of the house, agricultural work, and the animals. Lastocika, the main heroine in my novel, was exploited through work, but so were the other children around her. She was beaten, but so were the others. Maybe that's why there were other themes that preoccupied her.

You've mentioned in the past that you'd like to write a book about your grandmother's experience of being deported to Siberia. What was her story and have you thought about her in recent months? You said that in order to work on this book, you would need a trip to Siberia, to be able to understand what she would have gone through. Do you still want to take this journey?

My grandma got married very young, she had seven siblings. My great-grandmother raised them all on her own. My great-grandmother (whom I suspect was a Jewish refugee to Bessarabia) did not remarry, but she had no problem sacrificing her daughters in marriage, to help the boys in life. All the sisters were married to rich men. But my grandma was the "luckiest". My grandfather was the only son of a family with land and animals. The problem is that in those days wealth did not mean luxury, but also more work. Especially for women. So grandma stopped going to school; she had to work along with everyone on the land and tended to animals. Still, coming out of poverty, she always helped the poor. When the Soviets came, of course they were among the first on the list to be deported, but not only because of the land. First of all, because the one who drew up the lists in the village was a boy who had been in love with her in his youth. It was a kind of Bollywood film revenge. They stayed in Siberia for seven years and buried a child there. Grandma gave birth to him in the Taiga, but only an hour after giving birth, it was her turn to cut wood in the forest and the soldiers took her out of the barracks to fulfill her duty. They left Ionel there on the bench, and when their shift was over, they came home to a frozen child. Grandpa asked to bury him, but because the ground was watery, he did not manage to dig a hole for him, and threw him into a hole with water. Maybe this is where the fear of water comes from in our family. My mother was born after Stalin died, that's why she survived. They returned home to a hard life again, where they were ostracized for many more years as enemies of the people.

Grandma talked about Siberia all the time, but with few words. Hell, that's what she said. However, her hatred had to be camouflaged because (the tragedy of all children of deportees!) my mother needed to integrate into society, at school. So there was no open talk of the regime's evil. I think of their drama, of the fact that they could not hate openly. But my grandma hated as much as she could, in her own way: she celebrated religious holidays and she never spoke Russian. She hated a neighbor the most, who, after they’d been deported, entered the house and stole all the "good" spoons, forks, plates, and rugs. When grandma returned from Siberia, she saw them in her neighbor's house; even her skirts were worn by that woman. I think this was also a way to bear their pain — to hate the people who were closer, who hurt them less, but who were theirs. The betrayal of those close to us is the hardest thing to bear.

Siberia has become even more current, but in a bizarre way I feel even less prepared for this trip. My emotions today are different from the ones I started with five years ago. I don't know if it's good or bad. Emotions in general are always subjective and can load a story with a lot of unfairness. Logistically, this trip will have to be postponed, and emotionally it is better to wait. The book I would like to write is not the book of a single generation. It is my grandmother's book, but also my mother's book, and my daughter's book. We all have a place in this story, I wouldn't want my voice, which is shaking right now, to drag it all down.

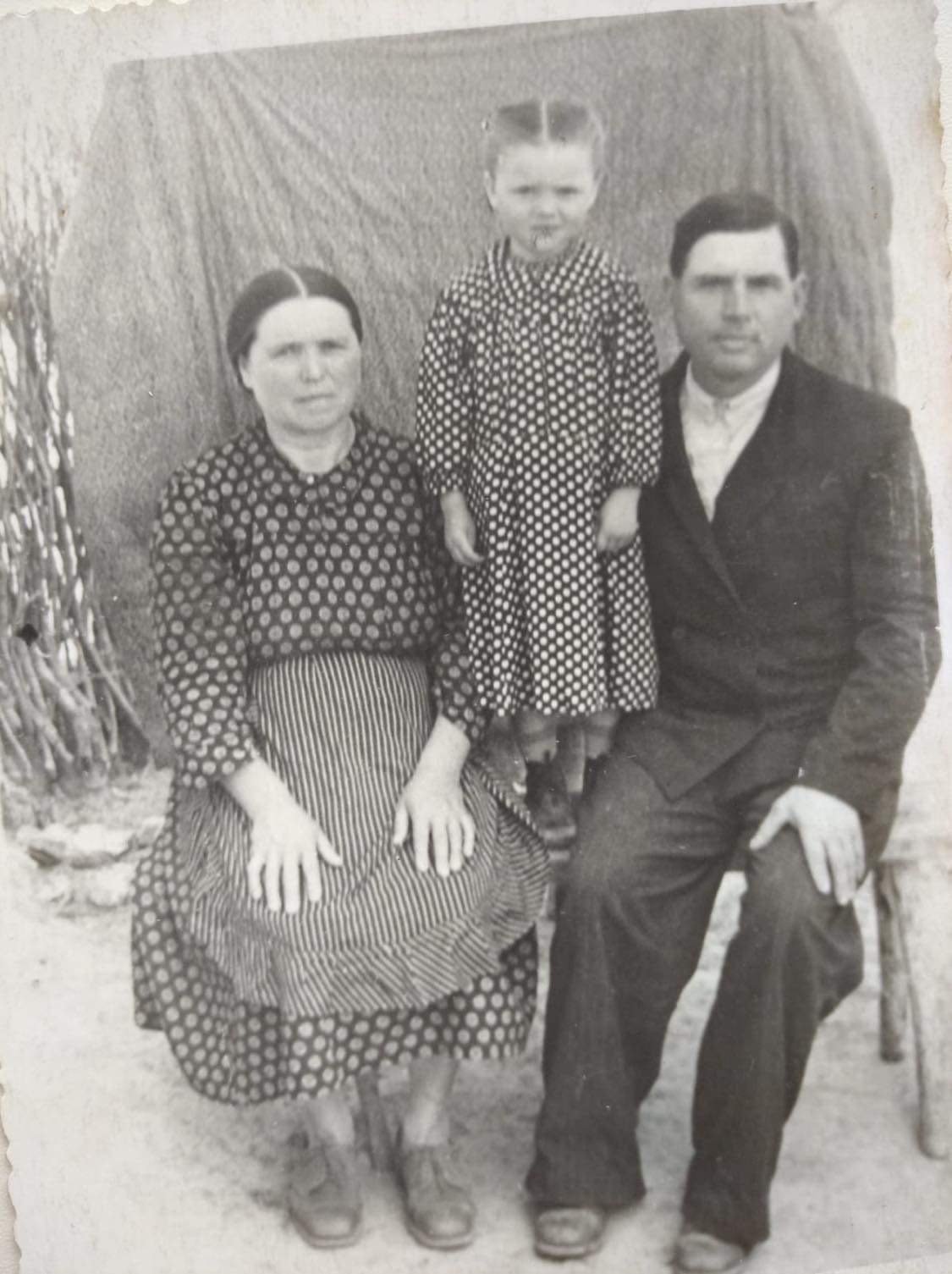

Pictured: Tatiana’s grandparents - Tatiana’s grandparents with her mother - Tatiana as a baby with her mother. Photos provided by Tatiana Țîbuleac.

I understand that you have also helped Ukrainian refugees in France, where you live now. What life stories or experiences have moved or surprised you over these past months, while you supported Ukrainians?

It scares me that in Europe we tend to talk about this war in the past tense, about what we did, and how we helped, when in fact it is still going on, when in fact it could go on for years. Speaking of stories that moved me, last week, a refugee who has already found work in the small town where I live came to the pharmacy to renew her medical prescription. She seemed resentful of being in France for six months! Some refugees I met here have returned to Ukraine. Others have integrated, found work, and their children go to local schools. We're talking more about women again — the women's war, which is not in the news, but is just as difficult.

My experience with refugees has had its ups and downs. With some of them I made friends, with others I did not. This is also a life lesson — all kinds of people run away from a war, not just those who share your own political beliefs. There were also cases when I met refugees who felt like they belonged to Russia, who believed that the fact that they had to leave their homes was the fault of the Ukrainian leadership. It is difficult to communicate with such people: in front of them, as victims, you cannot be right. But they were also helped along with the others and I think it's normal for that to happen.

You have relatives in Ukraine. How has life changed for your relatives?

Not for the better, obviously. But being closer to Moldova, they took refuge there, not in [Western] Europe. It's bizarre how sometimes, in extreme situations, we end up helping strangers, not close ones.

Your books are already translated into 15 languages, with great success particularly on the Spanish language publishing market. You do a lot of interviews for the international press. What are the questions you get asked the most? Was there any question that surprised you or revealed an unusual perception of Romania and Moldova? On the contrary, did you feel any cultural affinity that you didn't expect?

With The Summer When Mother Had Green Eyes it was simpler, although there were also different questions depending on the country. The book is most popular in the Hispanic world, where readers enjoy poetry and madness in prose. In the case of The Glass Garden, however, I was surprised by how little people know the history of Bessarabia, even in Romania, and I hope I don't set anyone on fire with this statement. I often need to make a short introduction about the so-called "Moldovan" language [invented by the Soviets in order to prevent national feelings with Romania], about the Cyrillic alphabet that we Bessarabians used, about the return to the Latin script [in 1989]. We have the impression that our history is known by everyone, but it is not. Then, also from the spectrum of curiosities, I was once asked why we didn't like having our language, Moldovan, and instead we always fought for the return to Romanian. In some countries, being able to speak a minority language is a matter of pride, many times people fight specifically for this, to preserve their identity, and again explanations are needed [on how 'Moldovan' was a colonial Russian tool]. But they are good questions that generate interesting discussions.

Romanian and Russian languages are characters in themselves in The Glass Garden. How do you feel navigating so many languages in your daily life today, writing in Romanian or, I guess, in English for the international press, living in France, speaking English with your family? (For example, I feel comfortable in both Romanian and English, but they also involve an effort to keep them up; I do not want to give any of them up, but that means that words do not always come to me in the language in which I am communicating at that moment; I gain a lot from this sway, but I also lose a bit of fluency. Maybe it's easier for you and your generation, because you already had this experience of navigating between Romanian and Russian since childhood.)

It is inevitable that a language goes through several phases, especially when we leave home. In my case, with Romanian, I went through numbness-revolt-longing-embarrassment-ambition. I have always read and written in Romanian, but I have not always spoken it and I have noticed that many times, especially among Romanians, I find it difficult to find a word or another. I know that some migrants idealize such situations, they see something exotic in forgetting your own language but I have always felt shame. On the other hand, English and French are more comfortable for me because they are more lenient with me. In English, I find it easy to be creative, in the sense that I don't care if I break one rule or another. I also admire this in my children, who play with their tongues, jumping from one to another with ease and without fear of getting slapped across their mouths. As Lastocika said, a language can also obey you out of love, not just out of fear. I'm still learning this.

An excerpt from GLASS GARDEN

You called me a sentimental bitch and I’ll chew you down to your mother’s milk for that.

xx

I’m a night birth. I’m seven years old. The woman says she’d carry me if her arms weren’t full. A blue light dangles from a tree and flickers on above me. I look back as we pass. The light is round like a loaf of bread, and the city gates look like a stone belly. I think, that’s the city. The road keeps going further down in the valley. The ice catches the bottoms of our feet, we move faster. The woman lets me hold onto her pocket so I can balance, so I can enjoy the view. The gentle light, the hidden stars! Blocks and blocks and blocks of apartments. Every last one, four high and four wide. The pocket is fluffy, and the tip of my finger starts to burn. The people’s lives look nice in the windows. Thousands of squares with pears in the middle. All in rows and columns. The people on the bottom hold the others by the shoulder. The people on the bottom are strong. A blue dog starts following us. Tiny pawprints in the snow. That’s the city, I think, everything’s in fours and blue. Don’t get left behind. I can’t be left behind. We stop at a fence. Закрой глаза и забудь всё. I can’t understand and I can’t remember a thing.

xx

The morning I woke in the woman’s bed was like no other. I slept right in the middle like a nut in chocolate. We could have fit five girls in there if we had to. That’s what candies live like, I thought. They live in crackling layers before a mouth closes around them. All I had at the orphanage was a blanket, and it smelled like mice. Some had it worse. Objects around me would radiate light like I’d never seen. The chairs, the walls. The world outside the window was new. A branch beaded with berries. A magical creature. Soaring treetops and birds in the sky. I heard a voice. Ты проснулась? The sound slid into my left ribs like a key and opened me. I got out of bed to find a mother. The joy of no longer being an orphan mixed with the horror of becoming an orphan again. Ласточка, she said, and that’s what she called me.

We ate three meals. Her afternoon tea was fragrant. Her bread, her butter, her honey. I ate so much that my left side started to hurt. The gas burned over the stove like a blue water lily. любовь, любовь, любовь, came over the radio. Tamara Pavlovna listened with a soft smile, and everything felt warm. She showed me the house as day turned to night. I take that thought with me everywhere I go. No amount of money or love could beat that. No one’s ever wanted me more. Not even you.

xx

Collecting glass wasn’t a real job, but it was something. Tamara Pavlovna had a ladder in her head. People could climb up it or slide down. It was a meritocracy. The glass collectors were below mail carriers, but over kvass vendors. Letters had real value. Once you drank the kvass, on the other hand, it was gone forever. A bottle could make you money, even if it was empty, even if someone pissed in it, even if it wasn’t yours, so long as you weren’t drunk or lazy, and we weren’t. We knew what we had to do and we did it. Our hands froze, our stomach’s wretched from the smell, but it was free money. Earnings. It kept Tamara Pavlovna around, kept her raising me. She didn’t do it out of the goodness of her heart. I noticed that in a matter of months. It was for the money.

Tamara Pavlovna got older. She said she needed help. I suspected what she really wanted was gratitude. That’s what all parents and pet owners want, so I gave it to her. I still do. She can have it. Tamara Pavlovna was selfish, but she was the only mother I had. There’s no point. I’d sooner take a blind man to the top of a mountain or cover a corpse with roses. I stopped wanting anything from the woman. She did care. I know that. Tamara Pavlovna did have a heart, but it wasn’t like mine. Hers sought gold, mine sought stars. Would she cry if she read this, I thought. Yes. Bitterness is hard to swallow. You can’t forgive. You can’t argue.

xx

I learned later that Tamara Pavlovna didn’t save me from the orphanage; she bought me. The idea gnawed at me for a few years. I should have asked the woman how much she paid, but I didn’t. I could have converted the money into bottles to see how much I was worth. I could have taken the bottles and smashed them over your head. I could have broken you like you broke me. It’s wrong to speak ill of Tamara Pavlovna. That’s one of the reasons I hate you. Sometimes it feels like if I hated you just a tiny bit more, my hatred would turn into love. It’s my greatest fear, so I leave things unsettled.

xx

I hung the clothes out to dry and stood guard on the street corner. During the summer, Șurocika would be the lookout from her balcony, but it was too cold in the winter. I couldn’t imagine someone grabbing my old, frozen clothes and running off with them, but I didn’t object. I wanted a break from rummaging for bottles. I called out, “pss, pss, pss,” and Morkovka would appear to curl up on my lap. Winters have changed since then, so have the cats. She was a magical creature!

That evening, I brought out the big basket, gathered the clothes, and wrapped the clothesline around my neck. It took me several trips. What I could neatly pack into a closet took up several feet on the clothesline. I started with the frozen curtains. It was like moving doors. I had to look behind me to make sure I didn’t swing them into a parked car or a pole. Tamara Pavlovna would have thrown a fit and made me wash them again. The frozen knitting and embroidery could crack, and I had to be careful with those, too. The embroidered TV cover snapped, and I was invisible for the rest of winter. The living room tablecloth was my favorite item in the house. It was round and had yellow-gold silk that was knotted around the edges. Mihail brought for Tamara Pavlovna’s birthday, which made it all the more special. I was in love with that tablecloth. As I carried it in the apartment, it held its perfect round shape, like a sun, slicing through the cold.

xx

I’m cleared-eyed about Tamara. I know that when I’m old, I’ll be as isolated as a leper. I know that all the fears I’ve locked away will break free like a pack of wolves and hunt me down. It’s oddly comforting to expect to be alone at the end, to expect the people you’ve wasted your time and money with to forget about you. It’s a relief to accept that the one you love is perfectly justified in abandoning you, to accept that unfulfillment isn’t yours or anyone else’s fault. I can’t see now that Tamara couldn’t have taken care of me. I love her even more for it. I love her hopelessly. What difference does it make that she raised me? That I brought her water? That I put a wet rag on her head? I was in the psyche ward, Tamara was at the E.R. Who’s watching in the end? Are you?

xx

How much do you need to remember before you become an alcoholic? How many betrayals does it take to harden a child’s heart? I shouldn’t have become a doctor. After Tamara Pavlovna, I shouldn’t be around other people’s children. I see how vulnerable they are at birth and think, at least they’ll be happy. They have mothers and fathers. They have money. I see how they latch onto their mothers and suckle like puppies. Why should a hungry child care about my pain? I can see the cruelty already. It grows like a red flower. Cruelty grows faster than fingernails, hair, or teeth. I went to see the woman who delivered a stillborn boy. She said she feels like a mother. Death just accelerated things. “We all wind up in the same place, the living, the dead, the in-between.” I can still hear her voice. I want them to be true to me. The in-between. Death will have her way, but what happens when you lose parts of your life? You can see you’re alive, but life takes a look at you and lines you up with the dead. I’m in-between. Tamara Pavlovna is in-between. I’ve always been in-between. If I could go back and change things, I’d free myself from love.

xx

Some people cannot live without stories. For these beautiful, sometimes insane people, all of life needs to be a story. They know that only in the body of a story can they tolerate the evil, pain, sickness, and betrayal nestled between the ribs. These people know that even the shortest, saddest story will not leave things unresolved. They know it will always be put right.

Translated by Andrew Davidson-Novosivschei